Accelerating the Front End of your Innovation process

The folks at Innovate Carolina have been putting on great conferences on innovation for a few years now, and they have another coming up in RTP in April. http://www.innovatecarolina.org/2017-conference-1/

The theme for this one is “Accelerating Ideas to Market” which sounds like something we’d all be interested in, and I was especially intrigued by this supporting concept they promise to explore:

“How do we do a better job speeding up innovation in the “front end”, generating and evaluating more ideas more quickly, without narrowing the scope of the ideas or simply making innovation processes more efficient but less disruptive?”

Since considering this question from the perspectiveS of a serial entrepreneur and a student of creative work—and after I took it for a walk and stared at the color green for 30 seconds two or three times—my thoughts settled into two clusters that I think could be equally useful as starting points for your ruminations.

One cluster takes shape when we first answer that conceptual question with another question, so let’s start by asking ‘What are your reasons for speeding up the front end?’

We must ask that question because there is a wonderfully creative answer to it, but you have to be fully appreciative of this answer to enjoy the fundamental advantages it offers.

If we can agree that we are the most ignorant we will be about a new opportunity or challenge at the very beginning of the innovation process then can we agree that the best reason for speeding up the very first steps of any innovation process is to get as smart as we can as fast as we can about what is most significant to our successful development of this opportunity?

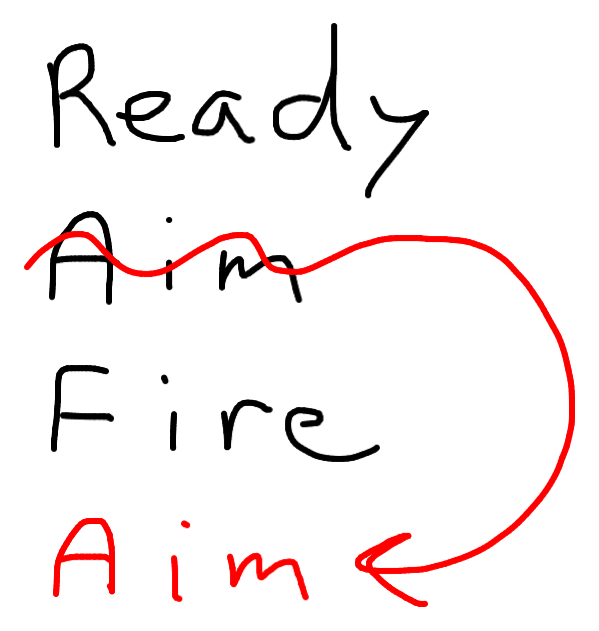

If so, that means less time spent predicting and planning and immediate time invested in a bias for creative action, a bias that is neatly captured in the re-ordering of Ready Aim Fire as Ready Fire Aim, because the fastest way to learn the most useful knowledge is to take action in the market or within the organization as soon as we possibly can so we can analyze what happens when we do.

It’s important enough to restate: To develop that most valuable early asset we can have in an innovation project—which is relevant and proprietary knowledge about the nature of the opportunity—we act quickly and ask questions as we do, and we think about what we just witnessed while we act again, this time asking better questions because we’re growing wiser.

And while others are planning we are beginning to discover all that we might do on our way to the most productive understanding of what we should do.

The second cluster of thinking serves the first. It begins when you imagine your organization is committed to the continual improvement of the creative and entrepreneurial qualities of the folks who work there. Doesn’t it make sense that a team made up of individual members who are intentionally growing their creative capacities and developing their entrepreneurial instincts will outperform a team whose members haven’t?

The front end of an innovation process will be quicker, more thorough, and more imaginative—both more efficient and effective—and the whole innovation process will benefit as well, when the team members are also working intentionally to develop their creative and entrepreneurial qualities.

And again, this seems important enough to try to understand it another way. Pick the band you loved to listen to because their creative riffs were uniquely theirs, and then think about all the hours the band member invested in the mastery of their craft. Consider your favorite team, college or pro, and think about the percentage of time they invest in becoming better athletes, in season and out.

Every front end innovation process we will ever invest in from now on benefits when we decide to help team members become more creative in their thinking and their perspectiveS and entrepreneurial in their nature and their skills.